Apr 13

2016

First Year Demons: Educational Game vs. Story Game

Posted by: Becky Slitt | Comments (0)

This is Part 3 of a 3-part series of posts about the Hosted Game First Year Demons. In the first part, I talked about games in education, and why ChoiceScript games can be a good method for teaching about culture. In the second part, I talked about our process for developing the setting and story for First Year Demons. In this part, I’ll talk about the differences in design and story between the two versions of the game.

Educational Game vs. Story Game

An educational game – at least, this particular variety of educational game – is written with the intent of teaching specific information. That means that there must be explicitly right and wrong ways for the player to act, with the right way being to make choices that demonstrate mastery of the target information. This is which is completely different from the guiding philosophy of Choice of Games. In Choice of Games stories, there are no right or wrong answers, just different paths through the story, different approaches to solving problems, and different potential personalities for the PC. While some answers in a Choice of Games story can lead to more successful outcomes than others, these results are not designed to reinforce a way of thinking or endorse any particular set of choices. However, in an educational game, it would be confusing and discouraging to the learner if making choices consistent with the curriculum led to unsuccessful outcomes.

So for First Year Demons, I had to think entirely differently about choices. There had to be right and wrong answers: the right answer was the one that reflected the principles that we were trying to teach; the wrong answers were the ones that didn’t. Every time the player made a choice, the game had to show whether that choice was right or wrong, and why.

Two of the techniques I used for this were: 1) Feedback from other characters, and 2) Restricting choices.

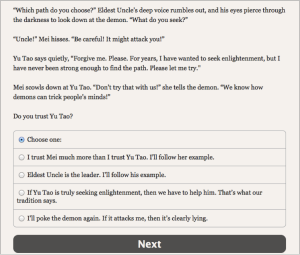

Here’s an example of the first technique: feedback from other characters. To illustrate the cultural importance of showing respect for elder relatives, I set up the following scenario in the opening scene:

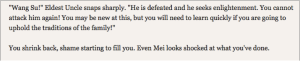

To attack the demon again would clearly be disobeying the PC’s uncle, which goes against the traditional value of filial piety that we were trying to teach. If the PC chooses that option, they get the following response:

Eldest Uncle’s words show the player that they have made the wrong choice; his anger and Mei’s shock reinforce the PC’s transgression of cultural norms.

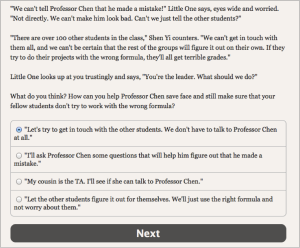

The second technique was to convey cultural information by restricting the options available to the PC. Here’s an example from later on in the game: the PC has just discovered that their professor made a mistake, and is talking to their friends about what to do.

Here, the options are limited in two ways, both of which communicate the cultural values that we wanted the player to learn.

First, asking the professor directly is ruled out by an NPC before the options are given: it would be a terrible breach of cultural norms to embarrass a teacher (or elder relative, or anyone in a position of power) by calling attention to their mistake.

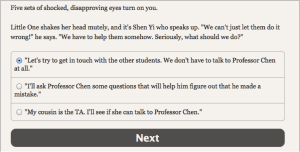

Second, if the PC suggests that they and their friends should let the other students fend for themselves, the NPCs rule that out, too:

This scene comes relatively late in the game, so by this point the player should have learned the importance of the cultural value of interdependence. A Chinese student in this situation would not only want to help their professor save face, but would also want to help their fellow students with the additional information that they’d learned. Therefore, the “wrong” option was available, but presented penalties for the player if they chose it. Suggesting that they keep that information to themselves is a breach of that cultural norm – which the NPCs show by their reaction, and which the game shows by its insistence that the player select another option.

The Final Version

First Year Demons now exists in two versions: the one originally developed for the educational project, and the one that’s more typical of the ChoiceScript style. A large part of the process of turning the first into the second consisted of relaxing the choice restrictions and narrative techniques that made First Year Demons an educational tool and part of a controlled experiment.

I’ll try not to give too many spoilers, because I hope you’ll play the game! But here is a general discussion of what I did.

I reduced the number of cultural factors that were tracked as stats, and added in stats that tracked weapons and magic skills. I also added stats that tracked the PC’s relationships with various NPCs. Those changes allowed me to make the story much more dynamic: the NPCs’ conversations with the PC could differ based on the strength of their relationship, and the PC could succeed or fail at different tasks based on their skills.

I cut some of the most obviously instructional choices, and included an opportunity for the player to choose the “wrong” option – ie, the one that doesn’t conform to Chinese cultural norms. For instance, in the scene I discussed above, the new version actually lets the PC be selfish enough to keep the correct information to themselves.

I added many more potential endings: total victories, total failures, and partial victories. Plus, there were multiple shadings within those endings to take into account the PC’s relationships with different NPCs as well as the different skills and personality traits that they’d built up over the game.

You can play both versions: go ahead and see what’s different!

What’s Next?

I hope that more educators at all levels will take advantage of ChoiceScript as a teaching tool. Given their strengths in conveying cultural information, ChoiceScript games would be a natural fit for teaching history: students could learn about history by navigating a story set in the past, or explore elements of historical causality by imagining what would happen if they make different choices from those made by real historical figures.

It’s encouraging and exciting to see that immersive games are already being used in some classrooms to teach language and culture. At Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, students have to speak Chinese in an Alternate Reality Game as part of their class and exam. And at Brooklyn International High School, students new to the US learn about their new country’s history through immersive digital games.

More educational projects using ChoiceScript are in the works, too. Are you using ChoiceScript in your classroom? Have you written an educational game? Let us know!

—

Supported by the Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) via Department of Interior, Interior Business Center, contract number D13PC00246. The U.S. government is authorized to reproduce and distribute reprints for Governmental purposes notwithstanding any copyright annotation thereon. Disclaimer: The views and conclusions contained herein are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as necessarily representing the official policies or endorsements, either expressed or implied, of IARPA, DOI/IBC, or the U.S. Government.

Steam

Steam Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook Tumblr

Tumblr RSS Feed

RSS Feed